|

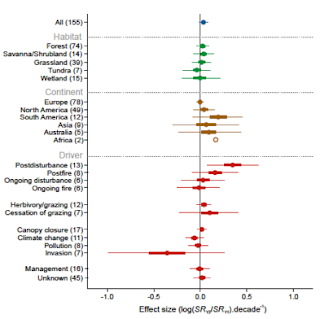

| Postdisturbance promotes diversity, whilst invasion seems to limit it. Source: Vellend et al., 2014 |

However, it is arguable that as the error margins cross zero, it is weak evidence for the derogatory effect of invasive species. Indeed, recent thinking has been that the impacts of invasions are not as significant as we have traditionally thought. Often primary production can be enhanced, and resident species do not always decline, overall less than half of the impacts were found to be statistically significant. The study which this post focuses on, published earlier this year, focuses on the impact of invasive plant species in Great Britain. Across 479, sites, Thomas and Palmer found that diversity had actually increased, and that the negative impacts of invasive plants on British biodiversity had arguably been exaggerated.

|

| Increased diversity of native species with non-natives, Source: Thomas and Palmer, 2015 |

Whilst their data is sound, I am inclined to disagree with their sentiment. Invasive species, particularly fauna but some flora as well, have had well documented negative impacts on native British ecosystems. Overall diversity can be a very crude measure of the health or success of an ecosystem, the composition is far more important - particularly if we are looking to safeguard our native biota. Yes, there may have been an increase in biodiversity, but is it the biodiversity we want? These patterns are not unexpected, invaders are particularly successful in frequently disturbed areas, which are also likely to be diverse areas due to the variety of niches to be exploited by fast growing colonisers. Indeed, if these areas are regularly disturbed, it will likely prevent competitive exclusion by the invaders and maintain diversity. This kind of ecosystem is far removed from our native climatic community of oak woodland. Perhaps I'm old fashioned, but I believe that our goals in conservation should be to maintain these native conditions as much as possible, rather than simply to maximise diversity.

Many examples of invaders, outside of the infamous grey squirrel, exist and are key issues in current British conservation. The American Mink, which has all but wiped out our native Water Voles - diminishing populations by up to 94%. The signal crayfish, larger and more aggressive than to our native white clawed crayfish, are estimated to have reduced native numbers by 95%. The aptly named Killer Shrimp spreads rapidly throughout freshwater ecosystems and has been shown to drastically decrease invertebrate and fish diversity, leading to simplification of food webs. Plants, as well, have had severe ecological consequences as invaders. Top of the most wanted list is Japanese Knotweed, which overruns fluvial ecosystems as well as much of our urban environment. There is even an invasive mouse which eats the chicks of a critically endangered Albatross species alive, documented in the British Overseas Territory Gough Island. The list goes on. The point is that there are many, many species which have and will have severe impacts on our native biota. The local lens must focus on what is actually happening in these local ecosystems, and we should be aware of what is happening to British wildlife before accepting sweeping generalizations that invaders have "no negative consequences for native diversity".

|

| Purposefully evil looking pictures of invasive species |