Earlier this week, we celebrated

World Soil Day (4th Dec). One of the key themes in this years festivities was to highlight the need to increase research into soil ecology and underground ecosystems. In particular, to warn of the potential

underground extinction risks that we have an very limited understanding of. A

new collection of papers has been published in Nature as part of World Soil Day to highlight these issues among other soil related discussions. So, in accordance, I will be bringing these issues to my blog to give us all an education about soil ecology, as despite the relative neglect compared other areas of ecology, the soil and its biota are fundamental components of all terrestrial ecosystems.

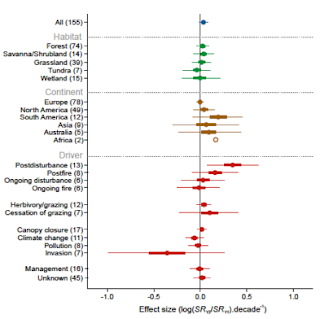

In order to form conservation approaches for underground ecosystems, we need a clearer understanding of the diversity and functionality of them. We know that soils provide vital ecosystem services, particularly for agriculture, so there is clear motive for conservation action - regardless of a lack of moral motive, as concern for things small and dirty tends to be less. The extent of biodiversity below ground is hugely unknown, partially due to the impracticalities of studying these organisms due to their size and inaccessible habitat. As shown in the graph below,

taken from one of the new papers, the vast majority of what lives in the soil is under 1mm in size. What the graphs also shows, however, is the extreme abundance of these organisms - over 1kg of bacteria per meter squared is an insane amount of individuals! Aside from our poor understanding of the diversity, other challenges for understanding potential extinction risks include the lack of suitable models, the complexity and density of microhabitats within the soil and uncertainty about temporal and spatial scales. I'm not going into these here, but they are all detailed

here if you're interested!

|

| Soil biota, shown by coloured crosses, are generally very small and very abundant ; Source. |

The most important extinction risk factors for soil organisms are not dissimilar to those faced by their terrestrial counterparts. Habitat loss, a concept we are all familiar with in relation to aboveground organisms, can cause equal disruption for soil ecosystems, for example through the fragmentation of the soil surface via urbanisation. This has been shown to link to declines in

abundance of nematodes and other soil biota. Equally, climate change and global warming pose a threat just as they do to terrestrial and marine biomes.

Extreme drought events can cause devastation of soil based habitats, for example. Climate change is also thought to have some more complex impacts on soils which can be equated to habitat loss, due to the degree to which the soils are changed. It has been shown that the

increased atmospheric CO2 concentrations lead to a reduction of nematode diversity due to the loss of pore spaces in the soil which are required by the organisms. Soil habitats are also impacted by agricultural practices, such as tilling, irrigation and fertilization which impact both soil structure and composition. It is thought that

these factors drive constant habitat loss for components of the subterranean community. Although it is difficult, as mentioned above, to know the extent of these impacts, we do know that

many of the susceptible species, such as earthworms and mycorrhizas, are of major functional importance to their own ecosystems and ours. There are also potential risks from invasive species, but at a microbial level more than invertebrate, which have likely been spread as a

result of travel and tourism. Many of the soil biota are highly specialized in their niche, which is commonly considered to make them

more vulnerable to both invasions and extinctions.

So there are considerable risk factors stacked up against soil ecosystems, much as there are against the terrestrial. There has, unfortunately, been very little conservation action in comparison. Some studies have already documented

local extinctions of earthworms and various fungi due to the factors discussed above. So perhaps we should start taking some action? This, if any, is a good time to start. 2015 is the

International Year of Soils, as declared by the UN General Assembly, after-all. This declaration was made with the intent to raise awareness of the life-supporting functions of soils and to promote the importance of soils in achieving a number of the new

17 Sustainable Development Goals. I hope that you've learned something about the oft-neglected but important goings on beneath our feet, and that in future you might give them a thought in conservation discussions.

Happy World Soil Day!

.JPG/1024px-EresusSandaliatusHogeVeluwe_(1).JPG)