Extinction is actually something we have gotten wrong in the past. For years, it was thought that coelacanths went extinct in the End-Cretaceous mass extinction 65 million years ago. In 1938, a living coelacanth was found in the western Indian Ocean and although it was a distinct species from the fossil variants, it was anatomically very similar and what is called a "living fossil". "Living fossils" are species that are, mostly superficially, morphologically similar to their extinct ancestors and are thought (wrongly) to have undergone little to no evolutionary change. Whilst these species may retain the plesiomorphic phenotypical states, it does not mean they are not still evolving and palaeontologists dislike the misleading using of the term in pop-sci press. Another species of coelacanth was discovered in South East Asia in 1997, cementing the idea that we were wrong, both about its apparent extinction and also its static evolution. Whilst this doesn't happen very often, it begs the question, what if we're wrong about other organisms?

|

| The Coelacanth, a "living fossil"; Source. |

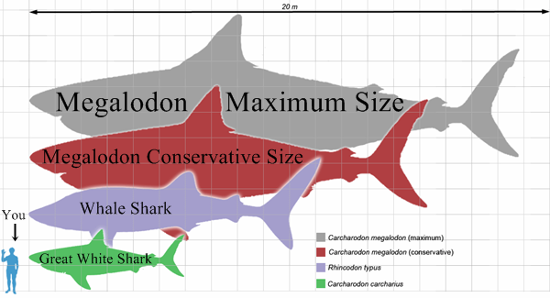

Two mockumentaries (fake documentaries) aired by the Discovery Channel over the last year or so attempt to answer exactly that question. The focus of the two programmes was the Megalodon, a gigantic shark which patrolled the seas between 15.9 - 2.6 million years ago. These are interesting programmes, but do have a tendency to spread misinformation, with 73% of viewers thinking that the Megalodon is still roaming our oceans. Many actual scientists, as oppose to the actors posing as scientists in the programme, were unhappy about the misrepresentation of palaeontological research, calling Discovery Channel "the rotting carcass of science on TV". Others, however, created a positive outcomes from the documentaries and worked on more robust mechanisms of estimating the extinction of the Megalodon, if only to put the rumours to bed once and for all. The authors, novelly, utilised a method that had previously been used to estimate the extinction of more modern species, such as the dodo. The method, a model called Optimal Linear Estimation (OLE), infers time to extinction from the temporal distribution of species sightings, or in the case, fossil instances. This method may not be applicable to all fossil taxa, but is an excellent step in out-of-the-box thinking towards a better extinction estimations.

|

| I wasn't joking about them being big; Source. |

Extinction is something we should be aware of and it can be a great tool to provoke changes in peoples outlook on human activity. Whilst "lazarus taxa", "living fossils" and the rest of it make for great sci-fi, their place in actual science should be profoundly separate from this.

Hi Ben,

ReplyDeleteFascinating post! 65 million years of extinction trounced by an unexpected find! The development of OLE is obviously of great importance, I hope such technological advancements can progress to smaller species - is there any talk of such a development?

Extinction is definitely something that has been taken-for-granted and after reading your post I think an increase in research is definitely needed!!

Hi Caitlin :) OLE is great model, but unfortunately relies on a good record of the species. Obviously, we have this for modern species which is why is intended for use with them. Fossil taxa can be problematic in this, but smaller species tend to have a slightly better chance of being preserved as they are more numerous - so I would think that OLE could potentially be applied to some of them. It really depends on the quality of the fossil record of the animal!

DeleteHi Ben!

ReplyDeleteWhat an interesting post! I loved the bit on "living fossils" - makes it sound so spooky and exciting! I was wondering what your own opinion is on "mockumentaries" and, more generally, the translation of science into popular media? I personally get seriously annoyed when things I've learnt in lectures or read in academic literature get grossly misrepresented on television or the internet - but do you think it could also be a force for good?

Popular media can be a terrible thing, but unfortunately it is what the average person has access to and will trust to provide them with accurate information. I think that there is a definite potential for it to be a force for good, however! A great example is to look at the turn around Discovery Channel have made in the last year. They took on board all the criticism they received over the Megalodon mockumentaries and similar shows, including one about the existence of mermaids. This year they've taken a stance to showing proper, informative and relevant documentaries like Racing Extinction. I think the lesson we can take away from that is that, as people who know better, we musn't let the media get away with spreading false information. It can be a force for good, but probably needs a fair bit of guidance from scientists.

DeleteHi Ben, a very interesting post! I always wondered (when I was young) how can scientists be sure that a species is truly extinct! Turns out they apparently cannot be 100% sure :)

ReplyDeleteMoreover, in regards to mockumentaries, I feel that yes they are misrepresenting however I think it helps people to gain interest and from there people may further research and learn more (even though I do get angry when data are false).

Lastly, when taking into account extinctions, although I agree with you that OLE is an out-of the box of determining extinction. However, I was wondering if you think OLE it is a sufficient way of researching extinction or if you believe more detail is needed rather than distribution of species sighting? I feel, that yes it is a good relationship to assess, however, I still believe there is some uncertainty to determine from this method if a species is extinct. Would there not be a possibility similar to the case of the coelacanth?

Thanks for your question Maria :) I think that whilst OLE is a good model, it won't be sufficient for all fossil taxa. As I mentioned in response to Cailin's comment, it relies on a good quality fossil record, which many species lack due to various preservation biases. What is great about the OLE approach was that it was trying something new and different instead of just relying on traditional methods - and that is what we need more of I think!

DeleteThere are cases similar to the coelacanth and I'm sure there will be more! Check out the Wikipedia on Lazarus taxa for a list of species that have seemingly "reappeared" after going extinct.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lazarus_taxon